Diaries from The Azores: Whale & Dolphin Conservation Expedition

Written by: Silvia Pisci

The Azores are one of the world’s prime whale and dolphin hotspots, with around 30% of all known cetacean species transiting here at some point during their migrations. They enjoy some good food and rest before proceeding to the colder waters of Northern Europe, or the Americas.Mid-March and spring shows no signs of arriving. Two flights and way too many bumps got me to Faial – one of the nine islands of the Azores Archipelago, which marks the westernmost point of Europe. In other words, I just arrived in the middle of nowhere out in the Atlantic, about 1,600 km off mainland Portugal.

When I was presented with the opportunity to join international conservation and citizen science NGO Biosphere Expeditions on a marine wildlife conservation trip to the Azores, I didn’t have to think about it twice. In no time, all my waterproof clothes were packed and a memorable Out of Office notice was switched on: “Dear friends and colleagues, off I go to find my big fish. I will reconnect with you once I return”.

Biosphere Expeditions is a non-profit organization that runs wildlife conservation research expeditions across the Earth. Their trips are nothing like leisurely holidays or safaris, but actual research expeditions placing ordinary people alongside scientists who are at the forefront of conservation work. The premise couldn’t sound more exciting to me, and once the small and picturesque city of Horta greeted my arrival, there was no other place on Earth I would have rather been.

Our expedition scientist is Lisa Steiner. She came to Faial for the first time in 1988, two weeks after her graduation, and has since then led an international research project on baleen whales. These mammals have been observed here fairly regularly from March to June over the past several years, but it is unknown where they have come from or where they are migrating to. Photo-identification is what enables scientists from all corners of the Atlantic to share a database of every single baleen whale spotted and record their migrations routes over the years.

What Lisa is doing almost single-handedly is to take pictures of all the whales she spots, outline the shape of their tails (the whales’ equivalent of fingerprints!) and send the photos to a research center in California, in the hope that a human scanner there will eventually say “it’s a match!”. It’s important, but labor-intensive work. And this is exactly where we come into play: nine people from the most diverse backgrounds and nationalities. A family lawyer, a nomad adventurer, a marine biology student, a pastry chef… it’s an almost women-only group, with the only exception of George, a Swiss gentleman whose need for adventure is still greater than his 83 (!) years of age.

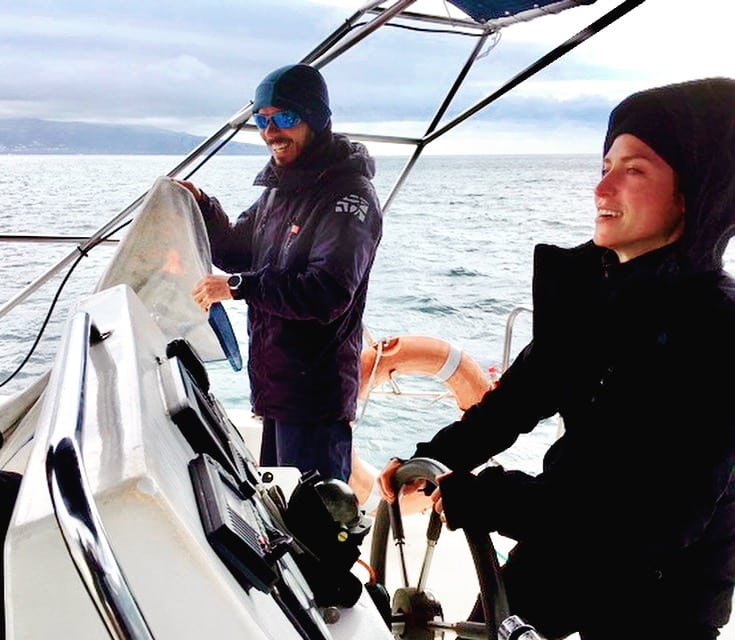

For ten days we plough the Azorean seas aboard a catamaran, rotating on duties such as spotting animals (whales, dolphins, turtles and birds) and recording data of all kinds (water temperature, wind direction, GPS coordinates…). But first – training to make us from a motley crew of individuals into a crew of citizen scientists that can be useful to Lisa. That includes learning how to use all the technical equipment, when and how all data needs to be recorded, plus specific information about the marine species involved in this project. It soon became apparent that my survival here would have dependent on how quickly I will make friends with Jairo, the skipper. And that was the first thing I did when I got on board our research vessel!

Unfortunately the weather was against us for almost all of the first week, hitting the island with strong winds and rain, preventing us from leaving the harbor on the scheduled time each morning.

Nonetheless, filled with bravery and seasickness pills, we ventured into the tumultuous waters and faced the cold winds each day with our hands and hopes tightly knotted to the boat. And for a long time it was us, the snowy profile of Pico’s volcano in the distance, and the infinite ocean all around.

As we’re floating on waters over 1,000 meters deep, a cold shiver ran down my spine: when was the last time I felt so small and defenseless at the sight of Nature? And what is it that makes this mix of fear and excitement so attractive?

I’m immersed in such reflections when we spot the shiny amber shell of a loggerhead turtle (or, as I would have called it until a couple of days ago, a common sea turtle). She floats next to our boat for a minute or so before dipping down into the blue. Beautiful creatures! How can we not admire them, brave adventurers and restless fighters, who travel thousands of kilometers across the oceans, following the currents and an innate sense of direction? They always know where they’re going and when it’s time to go back home. They struggle for life even before they see the light, and their entire existence is threatened by predators and perils of all kinds. In fact, only one out of a thousand will survive to adulthood. You, little one sailing on my side, you are my hero!

The more I learn about the marine species that we’re here to study, the more I’m fascinated by the similarities I see with human behaviors. The complexity of their bodies, their communication skills, the ways they socialize… Every species is different, and I am completely seduced by them all.

It’s our second day on the water when we spot a couple of Risso’s dolphins. Standing at the bow on my duty as “lookout person”, I couldn’t hold my excitement as I screamed “THEEERE!!” when

I saw the profile of the two fins emerging from the foamy waves. My discovery triggers frenetic data recording behind me (water temperature? GPS coordinates? wind direction?…), the “camera person” is trying to capture some good shoots, and I’m just standing, hypnotized by these enigmatic animals swimming next to me.

Due to their particular pigmentation, Risso’s dolphins carry on their skin the indelible marks of all their social interactions. Their body is a fascinating canvas of white lines reminiscent of Japanese calligraphy or Maori paintings, getting richer and richer over the years until their whole body eventually turns into white. They seem to be smiling when they swim away – if only I knew how to say “You’re so beautiful” in Risso’s language!

The week goes by and our chances of spotting whales are shrinking as the strong winds keep hitting Faial. Yet, we take advantage of every hour out at sea. We are now quite proficient in all duties onboard, we hold our positions with confidence and there’s a positive sense of synergy in everything we do. We made a great team, that’s for sure.

I say goodbye to the sea on my birthday. What a precious gift! Being on the water today carries ancestral feelings, and I am so deeply grateful to the intricate paths of life that brought me here today. You don’t always need to cross the ocean in order to connect to your deeper self, but sometimes you do, so I’m giving myself a pat on the back for making it all the way here.

The whales are here around somewhere, we’re hearing their “clicks” with a hydrophone, sometimes closer, sometimes further away. I keep straining my eyes out over the restless sea, as my thoughts descend into the deep to bid them farewell… It’s such a great privilege to share this space with you, dearest whales. I hope I’ll see you another time. I’d love to think that you’re free around here and enjoying some deserved rest between your long journeys.

It’s a calm sunny morning and I know I’m not the only one in the boat who’s treasuring this moment. We can’t hear the whales on our last day, but I think all our minds are at peace and with the sea. We we’re unlucky, sure, not to meet the whales. The other groups after us, and at the same time in the years before, had much better luck, seeing more whales species than you can shake a hydrophone at. Blue, sei, fin, sperm whales – you name it and we’re not jealous 😉 “Such is the nature of Nature!”, our expedition leader reminds us – so true, so beautifully, so unpredictable.

And there they come: a group of common dolphins approach our boat for the most spectacular goodbye of all. They may be fifty or more in total. Hanging out at the prow, I’m so close that I can hear them whistling! They sound like kids playing in the distance, until they emerge from the water surface in graceful twirls and pirouettes. The most perfectly-executed ballet could never do justice to the joyful elegance of these animals (or “non-human people” as many refer to them).

What a glorious ending to the trip. Another reminder that enjoying the journey is sometimes more important than reaching the goal.

As I fly over the ocean on my way back, it’s clear that this expedition has given me much more than I had imagined. Probably curiosity is innate in human beings, and the further we explore Nature, the more we discover ourselves. It all seems to make sense now: Lisa’s existence, confined to a small island and entirely devoted to research, and my endless craving for adventures of the wild around the world are more similar than I had felt initially. And the real key to evolution of oneself is, clearly, sharing the journey with a good team.